Bars, Restaurants, & Taverns

BUDDIES Post Tavern

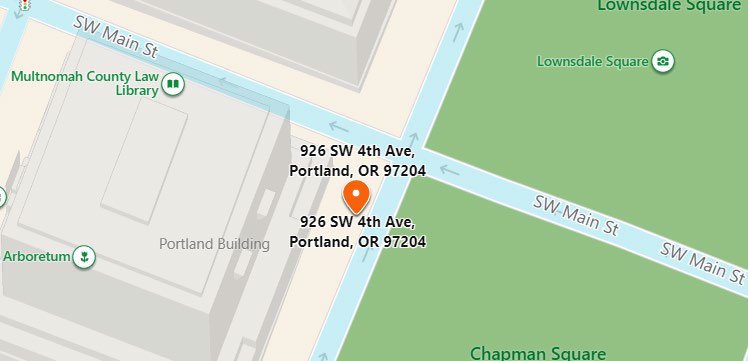

Same block as The Little Brown Jug. It was located just a short distance from Lownsdale Square and the Multnomah County Courthouse.

The bars, as now, needed licenses from the Oregon Liquor Control Commission. For that, they needed city council’s endorsement, which had rarely been a problem until the fall of 1964. Oregon police made a series of arrests for various sex and pornography offenses in 1963, which triggered a classic media panic, with Oregonian headlines like “They Prey on Boys.” Portland’s mayor, Terry Schrunk, decided the time had come for action.

Schrunk reigned as mayor for 16 years, somehow bridging the Eisenhower era, ’60s tumult, and the early ’70s. By 1964, he had already survived a racketeering scandal that led to a US Senate investigation and a trial in which US Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy testified against him. Boag classifies Schrunk, a Democrat, as a “breadwinner liberal,” favoring benevolent big government — for traditional households and citizens only.

By ’64, Schrunk had launched a Committee for Decent Literature and Films (!), and heated rhetoric swirled in city council meetings. Boag’s OHQ article culls some transcript gems: the police testified about women who “caress, kiss and fondle each other in public” at the Model Inn. Most riotously, 1 a.m. at the Harbor Club saw a huge crowd “packing it, with standing room only. From then on, all activities, such as males openly kissing each other, fondling each other, with no attempt to cover these activities.”

Schrunk and the council decided this would not stand (though one commissioner astutely noted that “these people are not going to disappear”). After a series of hearings in November and December, the city moved to shut down six bars, pressuring the OLCC to revoke their licenses.

“Everyone was shocked,” Cole remembers, “This was not how things had operated.”

James Damis was a young attorney, representing the Tel & Tel. “The owner bought it knowing it was a gay bar,” Damis, now 82 and still practicing law, recalls, “He ran it clean. He didn’t permit any hanky-panky.” The city’s move struck Damis, and other attorneys representing bar owners, as patently discriminatory. “I remember saying, ‘You can’t do that,’” Damis says, “And one commissioner saying, ‘We’re the city, we can do anything!’ Well, no.”

Damis and other attorneys pressed their arguments to the liquor commission. “We said it’s clear that this recommendation from the city is not because of any activity going on at the bar,” Damis remembers, “It’s simply because gay people congregate there. And that’s not constitutionally permissible.” According to Boag’s research, some attorneys involved in the situation cited the just-passed Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The denouement, then, was classically Portlandian: no billy clubs, no bold riots in the streets, just two rival bureaucracies and a well-framed legal argument. The unlikely agent of progress: the OLCC, which essentially dismissed the City of Portland’s attempt to crack down on “the Unmentionables” out of hand.

“I was surprised the OLCC had the guts,” Damis says now, “But they did.”

Schrunk sputtered. He wrote the governor, who ignored him. The only casualty, in the end, was the Harbor Club. When the city pulled its food license, the waterfront location shuttered.

“By 1967, nobody cared,” Cole says, of the year Darcelle XV opened in Old Town, “Gay bar. Lesbian bar. Drag bar. No one cared. By then, it was pretty open.”

In one odd (arguable) byproduct of the 1964 episode, the Portland bars’ survival may have muted activism. “In other cities, it was constant harassment,” Boag says, “In Portland, after 1964, the bars were left alone, and as a result Portland gays tended to be more lethargic politically. We never had a Stonewall.”

George Nicola notes that Portland’s first formal LGBTQ political organization, the Gay Liberation Front, didn’t organize until 1970, and arose from correspondence in a small alternative newspaper, Willamette Bridge, not any confrontation with The Man. Throughout the ’70s, as progressive bastions across the nation adopted both symbolic and actionable anti-discrimination measures, Portland and Oregon tended to move slowly. But quick or slow, it got better. By 1972, the Oregon Journal was running gingerly neutral stories (“‘Gays’ Here Almost Prim”). In 1977, the city formally recognized a gay pride day. (This year’s Pride Northwest festival and parade take place June 16 and 17.) Campaigns against ferociously bigoted early ’90s state ballot measures helped push Oregon politics in general onto their current progressive path.

Ironically, change came at the bar scene’s expense. The sanctuaries the city targeted in ’64 are now ghosts of the cityscape. A bank tower replaced the Dahl & Penne, where drag performers strutted before Darcelle XV; the Tel & Tel is now a social services agency. The Harbor Club’s premises now house Paddy’s, an Irish bar likely to see flush business during Fleet Week this month, no one the wiser.

“There was more entertainment—more shows and fun stuff—back then, and of course many more bars,” Cole says, “We’re down to what, five? And the reason is, we don’t have to have a bar. We can go everywhere. When you’re Darcelle, you get invited everywhere.”

Per papers that called Chronology of Portland’s Gay Bars – author unknown, “partly gay 1962-1966, listed I Darmron’s Guide 1966, Sadie Belmer 1968.”

Per Northwest Gay Review June 1977, “Closer to the Bus Depot, in one small area, was the Reed, Brown Jug, Rose City and Buddy’s Post Tavern. The area was like a public market, heavy with an invigorating smell of the sea. As with Dinty’s and The Lotus, they were hangouts for the Navy’s emissaries. Shopping for the market’s enticing morsels was a daily routine. Some of the salads tossed — fresh, green, or wilted — had more kick in its over-ripe 180 proof dressing than was in its basic seafood - (the tavern area is gone now , but the Post and Jug area is still an entertainment center — the Funland Arcade.) [Note Funland is now gone as well – it was on the corner of 3rd.]

MORE HISTORY COMING SOON

926 SW 4th

Years: (gay from at least 1962 to 1968)

citations & references:

City of Portland Directory, page 2281, 1940 – Buddies Post located at 815 SW Park Ave

City of Portland Directory, page 230, 1964 – Buddies Post Tavern at 926 SW 4th Ave

Listed in Damron Address Book/Address Guide 1965 under Bars/Clubs with notations of M –

mixed and RT – Raunchy Types [Hustlers, Drags, and other ‘Downtown Types’

Listed in Around The World with Kenneth Marlowe Magazine 1965

Listed in Damron Address Book/Address Guide 1966 under Bars/Clubs with notations of M –

mixed and RT – Raunchy Types [Hustlers, Drags, and other ‘Downtown Types’

Listed in Damron Address Book/Address Guide 1968 under Bars/Clubs with notations of M –

mixed and RT – Raunchy Types [Hustlers, Drags, and other ‘Downtown Types’

Listed in Damron Address Book/Address Guide 1969 under Bars/Clubs with notations of M –

mixed and RT – Raunchy Types [Hustlers, Drags, and other ‘Downtown Types’

Not listed Damron Address Book/Address Guide 1970 or thereafter

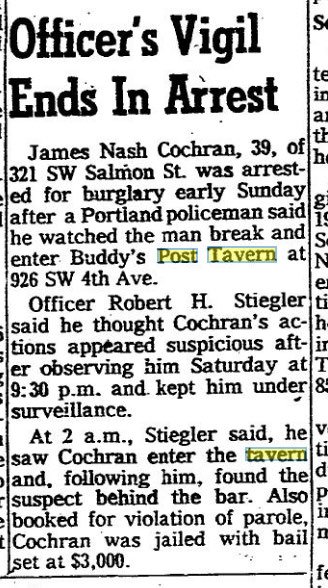

HOWEVER, per The Oregonian “One or the other may be the tavern which is referred to in an out-of-town gossip sheet’s report on vice conditions in Portland in early 1951. If this is the case, then obviously these taverns have a history much earlier than suspected. During this period, there is just a single reference to it in the Oregonian, one concerning a breaking and entering, Feb. 12, 1963, p. 15.